The commission, speaking through its in-house attorney, William “Creigh” Martson, denied the allegations

Two former employees of the Pennsylvania Game Commission say the commission’s Harrisburg headquarters fostered a toxic work environment in which the human relations department felt emboldened to target employees with harassment while upper management looked the other way. The commission called the claims “disingenuous.”

Both women say once health issues became part of their work lives — whether through disclosure, accommodation requests, or related discussions — they were met with escalating criticism and discipline. One quit, one was fired.

Even though they have moved on to other jobs, the pair requested anonymity in this article for fears of career retaliation beyond the PGC, but their identities are known to this outlet and were made known to the commission when approached for comment. Their claims were further bolstered by corroborating accounts from others as well as by scores of supporting documentation, much of which is shared in this article. Aliases are used to avoid confusion.

The commission, speaking through its in-house attorney, William “Creigh” Martson, denied the allegations, saying the commission “cares about its staff” and “is continually working to make the PGC a better workplace.”

Martson also complained that the commission was “being asked to enter the ring with its hands tied behind its back” given that it cannot discuss personnel matters due to confidentiality laws, and that taking the issue public was out of bounds.

“It’s disappointing that many, many years — and I mean years — that these folks have had their issue or even since they left the employ of the agency, that now they see fit to air their unilateral one-sided laundry in the media,” Martson said.

Sarah’s story

By 2021, Sarah says she loved her work at the PGC and took pride in the handful of promotions garnered along the way in 23 years of service.

Also on that path, a family member in 2017 began to worry over new postures they saw in Sarah, and recommended she see a doctor because of a family history with rheumatoid arthritis. That suddenly made sense to Sarah because at the time, she had been “burning through” her paid leave time on days she might come into the office late. An official diagnosis was not far behind.

Following her diagnosis, the toll of the arthritis became significant enough that action was unavoidable. She began using the federal Family and Medical Leave Act, or FMLA to cover her for some days she inevitably wound up making it into the office late. Later, after attending a statewide mandatory training for supervisors, she realized requesting an accommodation through the Americans with Disability Act would solve her problems and the PGC’s as well, theoretically, a win-win for both her and the commission.

“Modified hours were presented as a reasonable accommodation. I genuinely didn’t think it would be controversial,” she said. “I didn’t think it would be an issue because of that alternative work schedule that other employees had.”

In late December 2021, she submitted her paperwork for an ADA accommodation, a modest request that she be able to push her starting time back one hour because rheumatoid arthritis can be particularly difficult in the morning.

“I would feel like my ankles would be swollen. I wouldn’t be able to tie my sneakers or my shoes,” Sarah said about her mornings. “Walking, I felt like I was walking on rocks. Just getting up was painful.”

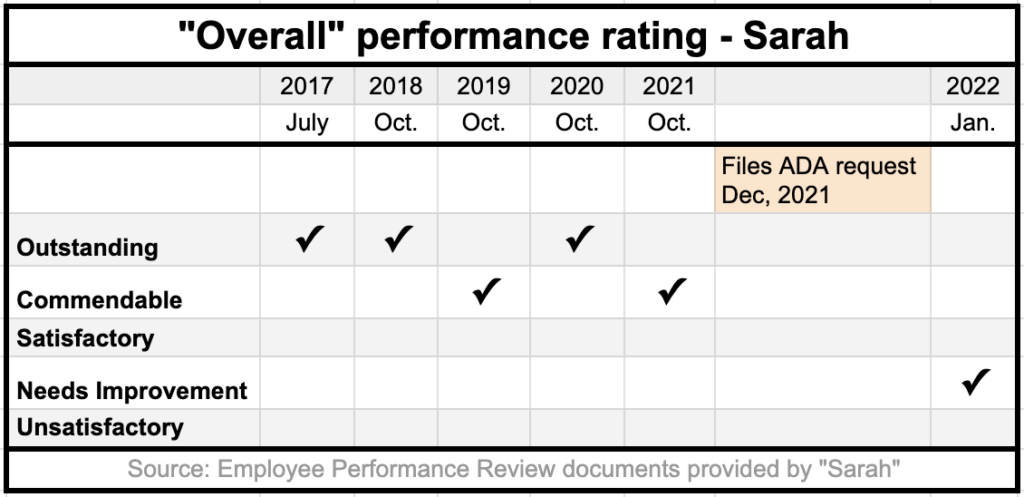

Her annual “Employee Performance Reports,” or EPRs, read like an employer’s dream, until that abruptly changed in the wake of the ADA request, submitted Dec. 27, 2021.

Eight days later, she was summoned for her first-ever pre-disciplinary conference in 23 years of service.

In all of the performance reviews from 2017 to 2021, her ratings were either “outstanding” or “commendable” — the top two rating categories provided on the review forms. Her reviewer frequently wrote praise such as, “Sarah continues to be an excellent employee in a position that can be very complex and demanding.”

Less than one month after the ADA request, she got a new performance review, notable because it interrupted the normal cycle of the annual reviews in early fall. Her overall rating dropped two grade levels from “Commendable” to “Needs Improvement.”

“How was I to know I wasn’t doing something correct if I wasn’t told before?” she wrote in her response on the document.

The commission declined to say how seriously or literal an employee should take an employee performance review to be, deferring the question to HR. “[Sarah’s] EPRs, whether they’re final, whether they’re interim, are written documents that speak for themselves,” Martson said.

Employment law experts call this “temporal proximity.” When a disciplinary action closely follows a worker’s request for a legally protected accommodation, the timing can be strong circumstantial evidence of retaliation.

“I went from an ‘outstanding’ evaluation to ‘needs improvement’ in the span of three months without a single meeting in between where anyone told me there was a problem,” she explained.

One person close to the situation who asked to remain anonymous for this article substantiated many of Sarah’s claims, and did not provide any information that would undermine any of her story. This person said as the situation grew more serious between Sarah and the HR office, her condition visibly deteriorated, with swelling and redness easily seen on her elbows and ankles, inflamed red fingers. This person agreed that Sarah was targeted, calling it an abuse of power.

Sarah said she began to feel so paranoid at work that she began refusing to leave her desk even to go to the bathroom.

Following that first pre-disciplinary conference in January 2022, the commission scheduled another seven pre-disciplinary conferences for Sarah through August 2023. “I loved my job,” Sarah said. “My work ethic was my identity. But physically and mentally, I couldn’t survive that environment anymore.”

When she left, she had 25 years of public service.

Melissa’s story

The PGC hired Melissa in a communications role in the summer of 2021. Prior to joining the commission, she enjoyed three years employment with a county government, a job she earned after interning there for two years.

The first several months of her employment at the PGC were smooth and uneventful, all of which slowly began to change with her health.

In February 2022, Melissa travelled with a cadre of coworkers to the National Wild Turkey Federation Show in Nashville. Not feeling well one night, she declined to stay with the team after hours in the Nashville nightlife and instead said she was going back to the hotel room.

“My direct supervisor said something to the fact that, and I can’t remember direct quotes anymore, but that I just didn’t want to be part of the team and I was just trying to be difficult because I didn’t want to stay out and get drunk with everyone,” Melissa recalls.

The ill feeling wasn’t a passing cold, or a bit of food poisoning that might quickly pass.

One month later, she was hospitalized with internal bleeding. The health problem wasn’t easily fixed and would linger with growing complications over the next several months. Sensing that her health was precarious, she expressed concerns about more upcoming travel, with the next event being a trip to Dallas.

Within weeks, Melissa says her work world was turned upside down, and the ominous warning she sensed from the remark in Nashville began to materialize.

Supervisors called her into a meeting on April 1, 2022, in which they questioned and criticized elements of her work, but Melissa counters that all of those projects and tasks had previously been approved by her superiors. Another such meeting on April 14 launched a stream of constant micromanagement that put her work product in a “no win” situation, she says.

In a letter, the PGC summoned Melissa to a pre-disciplinary conference on May 6, 2022. Its dating shows that she was being summoned into the pre-disciplinary conference on the same day as being informed.

When asked if three hours of notice for a PDC was sufficient and therefore acceptable, the commission declined to directly answer the question. Martson only pointed to a management directive which makes no prescriptions on how much advance notice of a PDC is required.

An email between supervisors on May 17, 2022 clearly indicates Melissa’s health was at least tangential to how supervisors were working through the situation. “We asked her about upcoming surgery dates, in which, she has none planned, at this time,” Krisinda Corbin, chief of strategic communications and outreach, wrote.

That same email suggested Melissa had stirred ire because of a social media post and clearly shows superiors were closely monitoring her social media.

“From what any of us can see/tell, she hasn’t posted any disparaging or negative posts to her own LinkedIn, as she previously was. Her personal Instagram and Facebook pages are still disabled, to the best of my knowledge,” Corbin said.

Melissa says she never posted — “would never post” — anything about the commission on LinkedIn. Emails she provided to Broad + Liberty show correspondence with LinkedIn regarding a ‘like’ on another user’s post – not original content – which she says was the source of the controversy.

Most critically in the email, Corbin praised Melissa three times, saying she “has improved on working independently,” that “she is making progress,” and “her independent work performance is improved.”

On the afternoon of May 17, she informed her managers of the work she had completed in advance of her leave, a vacation that was given final approval the next day. The PGC later cited incomplete pre-vacation work as its justification for termination.

Yet, despite these declared improvements, and without ever being placed on a performance improvement plan or receiving a single employee performance review, the PGC fired her seventeen days later on June 3, 2022. The firing came just after yet another pre-disciplinary conference on May 31 — in which the commission informed her on the same day, as with the earlier PDC.

“Between the pre-disciplinary conference [on May 6] and my termination… it was like less than… between eleven and thirteen days that I had actually worked,” she told Broad + Liberty. “So, if the goal is to really have improvement from an employee, I don’t think that’s adequate time.”

Two days before she was let go, Melissa met with then-director Brian Burhans, who later resigned in 2024 because of conflict-of-interest issues related to a moonlighting job. Her five pages of notes she took into that meeting were entered into evidence when she would later apply for unemployment.

“Somehow, I had two pre-disciplinary conferences now, the most recent being yesterday, that I have been completely blindsided by,” she wrote. “I brought the evidence to disprove the false allegations, including emails, but somehow the allegations still stood.”

One person well positioned to speak about Melissa’s case confirmed numerous elements of her timeline. That person, who requested anonymity because of fears of career blowback, also said that when Melissa was fired, it created an instant ripple across the commission, with colleagues expressing disbelief that she should have been fired.

“They took a job that was pretty much a dream job and they turned it into a complete nightmare,” Melissa said. “The agency you loved was turned into your own personal hell.”

Other accusations against PGC management, HR

Accusations of mismanagement and retaliation are not just limited to the core of workers at the Elmerton Ave. office. In January 2024, a number of game wardens aired grievances against the PGC’s leadership during a regular public meeting of the commission.

In 2022, a game warden applied for a posted promotion, and initially was the only applicant. At the end of the application period, however, the PGC posted the opening again, during which time a second applicant threw his hat in the ring. The first applicant then filed a labor complaint arguing that the PGC invented a reason to refresh the application process simply because they didn’t want him to get the job. In April 2024 the Pennsylvania Labor Relations Board agreed.

“Even more so, when the timing of the reposting and the alleged [reason to repost] are considered together, it is more than evident that the PGC was searching for a pretextual reason to preclude [applicant number one] from being the sole applicant for the LEC position,” it ruled.

The PGC also disciplined the first applicant for calling the second and explaining that a labor relations complaint would be filed. The labor board said that disciplinary action was borne out of “a discriminatory unlawful motive[.]”

The game wardens who spoke at the January 2024 meeting said the episode was emblematic of larger problems, especially with the HR office.

“Our officers do not feel their concerns are heard, that their work is undervalued, and more importantly, they collectively have lost confidence with members of senior staff who provide direction and oversight in the workplace,” said Game Warden Brian Witherite, a sergeant with 25 years at the commission and vice president of the Conservation Police Officers union.

Witherite added, “In my 15 years as a union official. I have never received the amount of feedback and level of frustration that the majority of our officers are conveying.”

Lieutenant Game Warden Jason Amory, then-president of FOP Lodge 114, echoed those sentiments.

“I feel it is important that the commissioners understand that this unfair labor practice decision is merely a symptom of a larger issue,” Amory said. “Our union has tried consistently over the last several years to negotiate with our human resources department and our agency’s management. We have been repeatedly ignored. Various members of our union have been lied to, threatened and retaliated against.”

The Labor Relations Board ordered the PGC to give the first applicant the promotion, pay him back wages with interest, and remove all records of the retaliatory discipline from his personnel file.

The complaints of retaliation and a hostile HR department from the wardens coincides with the same set of years in which Sarah and Melissa say they were targeted.

The Aftermath

In August 2023, Sarah gambled with her remaining leave days, taking them all at once to give her time to find a new job, which was a success. That job was also in government, and she says there have been no conduct or quality of work issues in the new job, and the arthritis is now in remission.

In April 2025, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission closed Sarah’s case stating it would not proceed further with its investigation but noting “this does not mean the claims have no merit.”

Since moving on to the new government employer, Sarah says she’s largely returned to the same person she was before the PGC drama. “I left and was promoted within a year at another agency. Nothing about my performance changed — just the workplace,” she said.

Melissa sent an email to the Pennsylvania Office of the Inspector General, and provided a copy of the concise, one-page complaint. The OIG, however, said in a reply letter it lacked jurisdiction, and thus as a matter of law had no choice but to ignore the matter.

Melissa considered filing an EEOC complaint, but didn’t go through with it largely because her life was still in so much turmoil at that time from a major surgery combined with losing her job.

After being denied unemployment benefits, Melissa appealed to the Pennsylvania Unemployment Compensation Board of Review. In June 2023, a referee ruled against her, finding “willful misconduct” based on the commission’s claims she failed to complete work assignments and didn’t use proper communication channels.

The referee’s decision made no mention of the May 17 email stating her performance had “improved,” her health issues, the social media monitoring, or her retaliation claims. Unemployment hearings determine only benefit eligibility, not whether discrimination occurred, and use employer-friendly standards that focus narrowly on workplace conduct rather than the broader circumstances of a termination.

The PGC also did not offer much in terms of how much advance notice of a PDC is appropriate. Given that the state is silent on how much time is needed, Martson said, “I think it would be frankly up to the management in terms of timing based upon the severity of any allegations, as well as any operational needs or requirements or other considerations that might be at play.”

Martson claimed the two women were unfairly tarnishing the commission by bringing their case to the media.

“It’s frustrating if not disappointing for the agency to have employees — and in the case of [Sarah] and [Melissa] — several years old allegations being brought and litigated through the media when both of these employees and every employee has more of an ample opportunity at identifying issues, working with the appropriate and responsible parties to rectify those issues, to be free from that kind of negativity. So it’s disappointing that many, many years — and I mean years — that these folks have had their issue or even since they left the employ of the agency, that now they see fit to air their unilateral one-sided laundry in the media,” Martson said.

“That’s their entitlement; that’s their prerogative. It’s just, it does the commission, of course, no favors to the extent that it has very tight restrictions on what it can and can’t say relative to personnel matters publicly, but that it tries to foster an atmosphere or a workplace environment of cooperation, of openness, of transparency.”

Adding a twist is the PGC’s unique position in the commonwealth. It is not a cabinet-level “department” such as the state health department or department of education. Instead, the PGC operates independently of the General Assembly’s day-to-day control. Its nine commission members are appointed by the governor and approved by the state senate. It does not rely exclusively on legislative appropriations because it is largely sustained by hunting and fishing licenses and other related fees. This does not make accountability obscure, but does give the commission extra distance from the kind of oversight other departments in the commonwealth might consider routine.

Everyone who spoke to this outlet about their story, or what they witnessed, all said the same thing about the PGC: It is largely a commission staffed with good people of good conscience who are extremely talented and devoted to the commission’s mission. The caveat, they allege, is that there is a small core of people who have had free reign to isolate and attack certain employees they don’t like, and that the commission’s upper reaches of management sat idly by.

If the allegations by Sarah and Melissa are accurate, the episode becomes one of those thematic moments where citizens may rightly ask whether the government lives up to the same laws it enforces on the public. The commonwealth does exercise some enforcement powers on disability discrimination, certain elements of the Americans with Disabilities Act, and more.

Todd Shepherd is Broad + Liberty’s chief investigative reporter. Send him tips at [email protected], or use his encrypted email at [email protected]. @shepherdreports