The printed circuit board assembly process has undergone revolutionary changes over the past three decades. What once relied primarily on manual component insertion and wave soldering has transformed into highly automated surface mount technology that enables the compact, powerful electronics we use daily. Understanding these assembly technologies—their capabilities, limitations, and appropriate applications—helps companies make informed manufacturing decisions.

Through-hole technology (THT) dominated electronics manufacturing from the 1950s through the 1980s. Components featured long wire leads that technicians inserted through holes drilled in PCBs, then soldered on the opposite side. This approach offered robust mechanical connections and straightforward visual inspection, making it ideal for the technology and quality control methods available at the time.

However, through-hole assembly imposed significant limitations. Components required substantial board space due to lead spacing requirements. Manual insertion processes limited production speeds. The drilling operation added manufacturing steps and costs. As consumer electronics demanded smaller devices with greater functionality, these constraints became increasingly problematic.

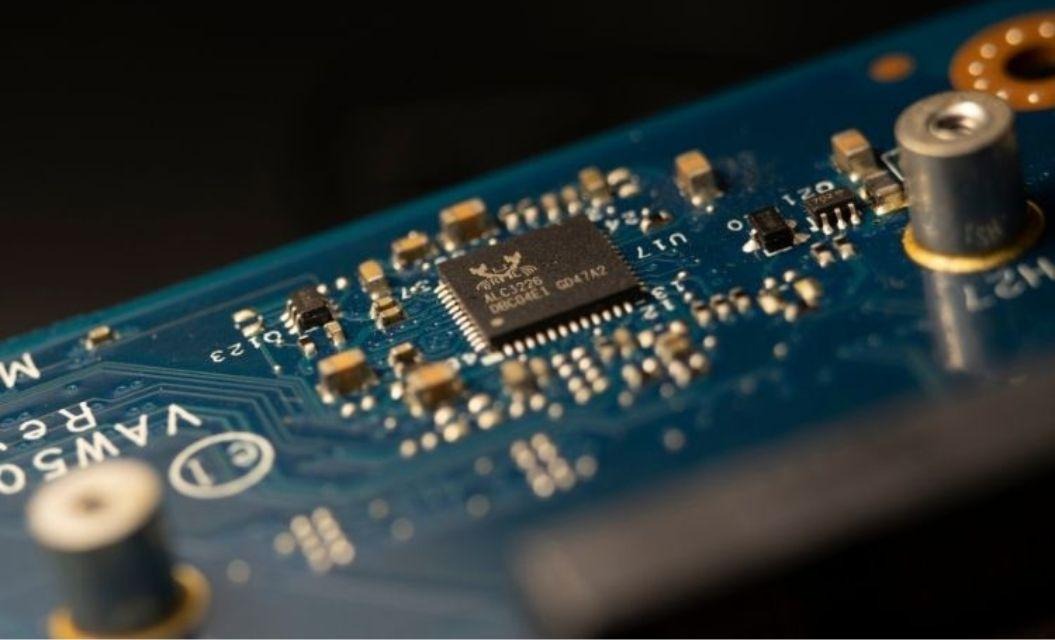

Surface Mount Technology (SMT) emerged as the solution. Instead of leads inserted through holes, SMT components feature small terminations that solder directly to PCB surface pads. This fundamental change enabled dramatic miniaturization, automated assembly, and higher circuit densities that revolutionized electronics manufacturing.

Modern SMT assembly services follow a precisely controlled process sequence that achieves remarkable accuracy and repeatability:

Solder paste application: Automated stencil printers deposit solder paste—a mixture of tiny solder spheres suspended in flux—onto PCB pads. The stencil, a thin metal sheet with apertures matching pad locations, determines paste volume and placement accuracy. Printer parameters including squeegee pressure, speed, and separation speed affect paste release and print quality.

Component placement: Pick-and-place machines retrieve components from tape-and-reel or tray feeders, check orientation using vision systems, and position them on solder paste deposits with precision measured in micrometers. Modern placement machines achieve speeds exceeding 100,000 components per hour while maintaining accuracy within ±25 microns.

Reflow soldering: The assembled board passes through a reflow oven containing multiple temperature zones. The carefully controlled thermal profile first preheats the assembly, then raises temperature above solder melting point to create metallurgical bonds, and finally cools the board at controlled rates. Profile optimization prevents defects like tombstoning, bridging, or inadequate solder joints.

Inspection: Automated optical inspection (AOI) systems examine every solder joint using high-resolution cameras and sophisticated image processing algorithms. They detect missing components, incorrect placements, polarity errors, insufficient or excessive solder, and bridging between adjacent pads. X-ray inspection verifies hidden joints under Ball Grid Array (BGA) and Quad Flat No-lead (QFN) packages.

This automated process achieves defect rates measured in parts per million while handling components as small as 0201 (0.6mm x 0.3mm) or even smaller 01005 packages used in the most miniaturized applications.

SMT's dominance in modern electronics manufacturing stems from multiple compelling advantages:

Miniaturization capability: SMT components occupy far less board space than through-hole equivalents. A 0603 resistor (1.6mm x 0.8mm) provides the same electrical function as a through-hole resistor measuring 6mm long with 2.5mm lead spacing. This size reduction enables compact product designs impossible with through-hole technology.

Higher component density: Without drilling holes that consume board space and create routing obstacles, PCB designers can place components on both board sides and route traces more efficiently. Modern smartphones contain over 1,000 components on boards measuring just a few square inches—impossible with through-hole assembly.

Improved high-frequency performance: SMT components feature shorter lead lengths, reducing parasitic inductance and capacitance that degrade high-frequency signal performance. This electrical advantage becomes critical in RF circuits, high-speed digital applications, and precision analog designs.

Manufacturing automation: Automated processes reduce labor costs, improve consistency, and accelerate production compared to manual through-hole assembly. A single placement line can assemble thousands of boards daily with minimal operator intervention.

Reduced weight: Eliminating component leads and associated hardware reduces assembly weight—important for portable devices, aerospace applications, and automotive electronics where every gram matters.

Lower costs at volume: While SMT requires higher initial equipment investment, the automated process delivers lower per-unit costs at production volumes, making it economically attractive for most products.

Despite SMT's advantages, through-hole technology remains relevant for specific applications:

High mechanical stress environments: Through-hole components soldered on both sides create extremely robust mechanical connections that withstand vibration, shock, and thermal cycling better than surface mount joints. Connectors, transformers, and power components in industrial, automotive, and military applications often use through-hole mounting for this reason.

High power applications: Large through-hole components dissipate heat more effectively than surface mount equivalents. Power supplies, motor controllers, and other high-current circuits frequently combine SMT control circuitry with through-hole power components.

Prototype and repair accessibility: Through-hole components are easier to manually place, remove, and replace—valuable during prototyping phases and for field repairs where automated equipment isn't available.

Cost considerations at low volumes: For very small production quantities, through-hole assembly may prove more economical since it doesn't require stencils, specialized placement equipment programming, or reflow oven profile development.

Many modern products employ both technologies, leveraging each approach's strengths. Mixed technology assemblies typically place SMT components first via the reflow process, then add through-hole components using selective soldering or hand soldering.

This combination maximizes design flexibility—engineers can use miniaturized SMT components for most circuitry while incorporating through-hole connectors, test points, or power components where appropriate. However, mixed assembly increases process complexity and costs compared to pure SMT.

Beyond the technical assembly process, companies must decide how to structure their manufacturing relationship. Two primary models exist:

Turnkey Assembly

Turnkey PCB assembly means the manufacturer handles everything—component procurement, inventory management, assembly, testing, and delivery of finished products. The customer provides design files and specifications; the manufacturer manages all production details.

Turnkey advantages:

Simplified management: Single point of contact eliminates coordination between multiple suppliers

Faster time-to-market: Manufacturers leverage established supplier relationships and procurement expertise

Reduced inventory risk: Manufacturer manages component inventory and associated carrying costs

Component expertise: Experienced buyers navigate supply chain challenges, identify alternatives during shortages, and optimize component selection

Economies of scale: Manufacturers pooling requirements across multiple customers achieve better pricing than individual companies

Turnkey considerations:

Less price transparency: Manufacturers mark up component costs, though potentially offset by their better pricing

Reduced control: Companies rely on manufacturer's component sourcing decisions

Intellectual property: Providing complete BOMs gives manufacturers comprehensive product knowledge

Consignment Assembly

Consignment (or kitted) assembly means the customer purchases and delivers all components to the manufacturer, who provides only assembly services.

Consignment advantages:

Component cost transparency: Companies see actual component pricing without markup

Direct supplier relationships: Maintains existing supplier partnerships and negotiated pricing agreements

Tighter component control: Companies approve every component source and lot

Better for proprietary components: When products include custom or proprietary parts unavailable through distribution

Consignment considerations:

Procurement burden: Customer assumes all sourcing responsibilities, requiring staff time and expertise Inventory risk: Customer owns components that may become obsolete or exceed requirements

Coordination complexity: Managing component delivery timing to match production schedules requires careful planning

Supply chain exposure: Customer rather than manufacturer absorbs impact of shortages or delays

Many companies start with consignment during prototyping and low volumes when procurement is manageable, then transition to turnkey as volumes increase and supply chain complexity grows.

Regardless of assembly technology or business model, several factors determine output quality:

Design for Manufacturing (DFM): The best assembly processes cannot overcome poor designs. DFM reviews identify issues before production—inadequate solder pad sizes, components too close to board edges, thermal management problems, or test point accessibility concerns. Manufacturers with strong engineering support add tremendous value through thorough DFM analysis.

Process control: Assembly involves dozens of process parameters—solder paste chemistry, stencil thickness, printing pressure, placement force, reflow temperature profile, and many others. Maintaining these parameters within specification through statistical process control (SPC) ensures consistent quality.

Incoming inspection: Component quality directly affects assembly quality. Counterfeit components, moisture-damaged packages, or parts outside electrical specifications cause defects. Rigorous incoming inspection catches problems before they compromise production.

Environmental controls: Temperature, humidity, and electrostatic discharge (ESD) all affect assembly quality. Climate-controlled facilities with proper ESD protection prevent moisture-related defects and component damage.

Operator training: Despite extensive automation, human expertise remains crucial. Well-trained technicians set up equipment correctly, recognize problems quickly, and maintain quality standards throughout production.

Choosing an assembly manufacturer requires evaluating multiple factors beyond price:

Technical capability: Does their equipment match your product's requirements? Can they handle your minimum component sizes, board complexity, and assembly volumes?

Quality systems: What certifications do they maintain (ISO 9001, ISO 13485, IATF 16949)? What defect rates do they actually achieve? Can they provide objective quality metrics?

Engineering support: Do they offer DFM reviews, component selection guidance, and failure analysis? Engineering expertise separates adequate manufacturers from excellent partners.

Supply chain strength: For turnkey assembly, evaluate their supplier relationships, component sourcing capabilities, and ability to navigate shortages or obsolescence issues.

Communication: Responsive, transparent communication indicates how the working relationship will function when problems inevitably arise.

Geographic considerations: Location affects shipping costs, lead times, time zone alignment, and visit feasibility. European manufacturers offer proximity advantages for companies serving European markets.

PCB assembly technology continues advancing. Industry 4.0 initiatives bring greater automation, real-time process monitoring, and data-driven quality improvements. Artificial intelligence optimizes placement programs and predicts quality issues before they occur. Advanced packaging technologies like system-in-package (SiP) integration increase functional density further.

However, fundamental principles remain constant—precise process control, thorough inspection, and experienced engineering support determine assembly quality regardless of technological advances. Companies that partner with manufacturers demonstrating these fundamentals position themselves for success both today and as technologies evolve.

Understanding assembly technologies, business models, and partner selection criteria enables informed decisions that affect product quality, costs, and market success. Whether launching a first product or optimizing established manufacturing relationships, this knowledge provides the foundation for effective electronics manufacturing strategies.